- Home

- Connilyn Cossette

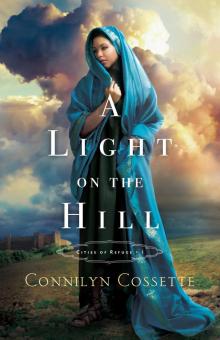

A Light on the Hill

A Light on the Hill Read online

© 2018 by Connilyn Cossette

Published by Bethany House Publishers

11400 Hampshire Avenue South

Bloomington, Minnesota 55438

www.bethanyhouse.com

Bethany House Publishers is a division of

Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan

www.bakerpublishinggroup.com

Ebook edition created 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

ISBN 978-1-4934-1361-4

Scripture quotations are from the New American Standard Bible®, copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. (www.Lockman.org)

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, incidents, and dialogues are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Cover design by Jennifer Parker

Cover photography by Mike Habermann Photography, LLC

Map illustration by Samuel T. Campione

Author is represented by The Steve Laube Agency.

To Collin,

whose multitude of freckles are more precious than all the stars in the universe.

Being called your mother is a precious gift

and a high honor.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Cities of Refuge in Israel

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

A Note From the Author

Questions for Conversation

About the Author

Books by Connilyn Cossette

Back Ads

Back Cover

Then the LORD spoke to Joshua, saying, “Speak to the sons of Israel, saying, ‘Designate the cities of refuge, of which I spoke to you through Moses, that the manslayer who kills any person unintentionally, without premeditation, may flee there, and they shall become your refuge from the avenger of blood.’”

Joshua 20:1–3

Cities of Refuge in Israel

Prologue

Jericho

1406 BC

The priest’s kohl-lined eyes glazed over as he held the iron brand in the center of cedar-fueled flames. Pressing my back against the column I was tied to, I clawed my nails into the wood.

“It will be over soon, little Hebrew,” said the man with painted lips, blood-red and curving with false tenderness. “And then you will belong to our Great Goddess, Ashtoreth.” He gestured to the crescent moon hovering low in the black sky. “There is no greater mistress. No higher calling than to be one with the Divine Lady of the Night. The Queen of Heaven. The Consort of Our Lord Ba’al.”

From the moment my friend Alanah and I had been kidnapped by Midianite traders from the Hebrew camp, I’d determined to cling to Yahweh—to the hope that somehow my people would rescue us from Jericho before they invaded. But after being stolen from the home of Alanah’s sister Rahab, where we’d taken refuge for the past few months, and tied to this Asherah pole in the courtyard of the temple, I’d been forced to acknowledge that Yahweh may not have heard my pleas, or deigned to answer.

“Stop toying with the girl, Reshbal. Finish it.” The ancient High Priestess looked on from the bottom step of the temple porch, disdain slathered across her face as thick as her overdone cosmetics. She flicked hennaed talons at me. “The king wants her first thing in the morning.”

The triumphant gleam in the woman’s black-rimmed eyes made my skin prickle. What would they do to me after they branded me like a beast? And why would the king of Jericho want to speak to a thirteen-year-old girl?

The priest tipped his head to his mistress, lifted the rod from the fire built upon a tall bronze brazier, and held it aloft as he sauntered toward me, bare-chested and tattoos swirling down his arms and up the sides of his shaved head. The branding iron glowed red-orange, outlining the symbols of Ba’al and Ashtoreth that would forever mark my flesh. I whimpered and slammed the back of my head against the wood, gripping the carved surface with desperation. If only there were something else to cling to instead of a towering cedar pole engraved with hideous gods.

The man’s kohl-blackened brows, stark against his pale skin, lifted as he dragged his dark eyes up and down my body. My shoulders jerked forward, as if by curving inward I could shield myself from his leering. Nausea flamed in my chest as my mind caught up with their earlier conversation. Now I knew. I knew what their plans were for me.

Yahweh! Yahweh!

“Now. My lovely. I would advise holding still. We wouldn’t want those fascinating silver eyes to be blinded, would we? Turn your face to the side now, like a good little girl.”

I could not have turned my head if I wanted to, convulsions paralyzed me. Yahweh . . . Yahweh . . .

“Please . . .” The silent entreaty formed on my lips, and I tasted the salt of my terror as tears slipped into my mouth. “No.”

The flames of the enormous brazier framed the priest on either side and the temple loomed behind, a many-toothed monster of stone and cedar waiting to consume me.

Yahweh . . . Yah . . . Even my prayers shuddered to a stop as the priest lifted the brand in the air with one hand and shoved my cheek against the column with a snarl. The metallic smell of the brand filled my nostrils as he chanted a foul blessing to his foul goddess.

The metal slammed against my cheek, searing my flesh in an explosion of pain that spiked to the soles of my feet and to every fingertip. I screamed as my head jerked and the edge of the brand slipped across the corner of my eyelid, digging fiery teeth into the tender skin. My knees gave way and I slumped sideways, the rope chafe on my wrists overtaken by fire-breathed agony. My addled mind floated my parents’ images across my hazed sight. “Abba! Ima!” I moaned, as if their hearts could hear my own. The fire dug deeper into my skin. It would never stop burning.

Kill me. Kill me, Yahweh. Have mercy.

A shout echoed across the temple courtyard, but I could see nothing past tears and fire. Someone was screaming at the priestess. Someone whose voice reminded me of home. I managed to pry my right eye open and push back against the haze that threatened to drag me into unconsciousness and recoiled again at the sight before me.

Mercy had arrived—not in the form of relief from my blazing torment, but in the form of an arrow through the eye of the priest on the ground in front of me. . . . I blinked again, attempting to clear my vision. . . . Alanah strode across the void, another copper-tipped missile nocked in her bow, aimed directly at the High Priestess o

f Jericho.

CHAPTER

One

7 Av

1399 BC

Shiloh, Israel

With one finger I followed the rippled path of shame down my face. The scarred ridge of the crescent moon of Ashtoreth cupped my cheekbone in a cruel embrace. One ray of the sun-wheel of Ba’al above it slashed across the corner of my eyelid, a constant reminder of how easily I could have been blinded when the High Priestess ordered me branded as a temple slave seven years ago. The fact that she’d been buried beneath the rubble of Jericho the next morning was no consolation. It did not erase the false accusation permanently burned into my skin—prostitute.

Shaking the word from my head, along with the memories of my time of captivity in Jericho before it fell, I knelt in front of the open-mouthed tannur oven. The flames that had sparked the horrific memory had died down, the coals now pulsing a steady glow within. After a wave of my hand over the embers to ensure the temperature was even, I slapped a few circles of dough around the walls of the oven and waited for them to begin to curl away from the blackened surface. The smell of acrid smoke tinged with yeasty bread was a comfort, completing the work of bringing me back to the present.

Built for some Canaanite woman and situated beneath a small hole in the ceiling to release smoke, this round, clay oven was the centerpiece of the house. Although I was grateful to no longer cook our daily bread on a flat rock next to a campfire in the wilderness, whenever I used the oven I wondered about the enemy woman whose hands used to press dough to its sides. Had she too looked out the same window, longing to be free of these four walls?

A sudden knock at the door halted my musings. I placed the last round of warm bread into a basket, my heart tapping out a tremulous beat as I called out “a moment please.” Then layering my linen headscarf over my hair, I twisted, tucked, and tied until most of my face was hidden behind a swath of sky blue. The ritual, accomplished every day for the last seven years without a mirror, was as familiar as it was frustrating. Only my eyes would be visible. Nothing left to judge.

I unlatched the door and pulled it open a handspan, enough to see that it was merely Yuval, my father’s steward. Relief steadied my runaway pulse.

“Shalom.” He dipped his head with his usual deference, a few threads of early silver hair glinting among his dark brown curls. Although Yuval rarely smiled, his narrow-set brown eyes communicated kindness and patience with my reluctance to open the door wider. “Your father asked that you come find him. He would like to speak with you.”

“In the vineyard? Why?” For the past few weeks my father had spent every waking moment among his vines, checking and rechecking for the precise moment the grapes would be ready for harvest. “He is not feeling poorly again, is he?”

My father’s most trusted servant shrugged without revealing his thoughts, although his relaxed manner assured me the summons was not overly urgent. Yuval would no more discuss my father’s secrets than cut off his own hand, even with me. With a gesture toward where I would find my father among the vines, he turned and walked away, his loyalty intact. I longed to run after him and beg for more information, but I could not chance coming across one of the new field hands who had not seen me before. I’d had enough of the staring and the pointing and the disparaging looks. These walls were as much a refuge as they were a prison.

Stalling, I placed a few pieces of bread into a small basket for my father, alongside a handful of briny olives and the herb-infused goat cheese he loved wrapped in a square of linen. Then I scooped the still-warm ashes from the oven into a large pot and tidied the room until I had nothing else to prevent me from venturing outside.

With a white-knuckled grip on the door handle, I took a few slow, deep breaths before stepping over the threshold into the blinding sunlight, basket in hand. Only after scanning the field for movement and listening for any nearby voices did I head for the place Yuval had indicated, counting each step to keep my mind occupied.

Long lines of vines trailed past our home, drenched in sunlight and heavy with fruit, sloping down the hillside. Just below the boundaries of our land, the Mishkan perched atop a small rise, the white linen fences of the Tent of Meeting undulating in the ever-present breeze that whispered through this valley. Squinting, I could still envision the shekinah presence of Yahweh that used to hover over its black covering until we’d entered Canaan and now resided only above the ark within the holiest place, hidden from view.

After searching row after row, I found my father with his back toward me, his knowing hands surveying the fruit of his tireless work of rebuilding the vineyard since the Amorites fled this valley nearly four years ago, leaving many charred and burning fields in their wake. Seeing the abundance possible after such deliberate destruction by our enemies gave me hope that our people might eventually flourish in this new land, yielding fruit for countless generations to come.

I walked down the path shaded by sprawling, twisted vines, inhaling the rich scent of the earth mixed with the sweet tinge of grapes readying for harvest. My father’s workers had been harvesting the crops and treading the grapes for days now. Only this small section remained unharvested, the vines that had been planted from seeds carried from Egypt. After three years of training the spindly new tendrils on piled rocks and low fences, pruning carefully, nourishing roots with ash, and coddling the buds when they finally poked tentative faces toward the sun—his labors had finally yielded wine-worthy grapes.

My abba had learned such techniques at the knee of his own father, an Egyptian vintner who’d tended Pharaoh’s own vines and who’d insisted he recite the steps, again and again, throughout the forty years they’d traveled in the wilderness.

My grandfather, having joined the Hebrews during the Great Exodus and committing his path to Yahweh, had hoped that someday his legacy would be planted in the Land of Promise—but his own eyes never saw the day. Instead my father, born at the foot of the mountain where our people entered into covenant with Yahweh, had completed the journey for him.

“Will the field hands begin picking these today?” I grasped a bunch, the red skins warm and silky in my palm. I twisted one of the globes from its home and popped it into my mouth. Sweetness exploded against my tongue, a reminder of the first time I’d ever eaten a grape whisking through my memory—a tantalizing taste while running through the Canaanite countryside with my friend Alanah, as we had tried to find our way back to the Hebrew camps—a moment that had sparked my fascination with every flavor and texture available in this land.

My father hummed as he bit a grape in half and checked the color of the flesh with his little finger. “Yes. These are finally ready.”

No matter that he was approaching his fiftieth year and that his attire was thoroughly Hebrew, my father’s posture and lanky build still announced his full-blooded Egyptian heritage. His black hair, although silvering at the temples, was thick and bound at the nape of his neck with a leather tie. His full beard brushed the top of his broad chest. A sudden memory of tangling my small fingers in his beard whispered through my mind, along with the honeyed memory of my mother’s laughter at his ridiculous antics and loud exclamations.

Since her death only a few months before, shortly after we’d left Gilgal to join my father here in Shiloh, the vineyard had become his solace. He buried his grief beneath the vines, watered the soil with silent tears, and spent hours every day walking up and down the rows, checking each plant with the same tenderness he’d offered my frail mother as she’d withered into nothing after a sudden illness had stripped her of strength.

Coming alongside him, I peered out of the corner of my eye to catch the curve of his smile before it diminished beneath the weight of his memories. What I wouldn’t do to hear the full breadth of his enveloping laughter again. “She would have been so proud. I wish she were here to see the first grapes from the seeds Grandfather carried out from Egypt being harvested.”

The pause before he spoke was louder than his words, as was the grief

still fresh on his face. “As do I,” he said, reaching out to slip his arm about my shoulder. “She had faith, even when I did not, that this vineyard could be salvaged and that my father’s withered, forty-year-old seeds would miraculously sprout.”

We stood together, breathing in tandem. The safety I’d always felt beneath the shelter of my father’s arm was no different now than it had been when I was a little girl. Even when I’d been a captive in Jericho, I had only to summon the sensation of being tucked against his body, with the warm rumble of his voice against my cheek, to feel a measure of calm.

He cleared his throat before speaking. “Yehoshua will be calling an assembly this afternoon.”

“Have the men surveying the tribal lands finally returned?” A team of soldiers, mapmakers, and scribes—three men from each of the seven tribes that had yet to receive their portion of the land—had set out months ago to walk the length and breadth of this newly conquered country. They had been due back for weeks and feared captured along the way.

“They have.” His gaze slipped away from me and toward the ground, his fingers feathering through the end of his long beard. “Yehoshua has been debriefing them for the past couple of days. Soon they will begin casting lots to determine which cities will be allotted to each tribe.”

“So it will all be up to chance?”

“No, daughter, it will be up to Yahweh which tribe settles in which area.”

“We won’t be forced to move, will we? Not after Yehoshua rewarded you for your faithful service with this land? After all the work you’ve done to revive this vineyard?”

“No. Shiloh is to remain the permanent home of the Mishkan, a holy place tended by the Levites, and this vineyard will continue to supply wine for the offerings and celebrations.”

“But aren’t you concerned that—”

He turned to me, cutting me off with a sweep of his long arm toward the Mishkan. “Let us leave those worries to Yehoshua. For now . . . I must speak with you about a matter.” He pulled in a wavering breath through his nose, as if his thoughts pained him.

Until the Mountains Fall

Until the Mountains Fall Between the Wild Branches

Between the Wild Branches To Dwell among Cedars

To Dwell among Cedars Counted With the Stars

Counted With the Stars Shelter of the Most High

Shelter of the Most High Shadow of the Storm

Shadow of the Storm A Light on the Hill

A Light on the Hill Wings of the Wind

Wings of the Wind